A core component of a premarket submission is clinical evidence. Clinical evidence is gathered through a process of clinical validation, which involves gathering data on the safety and effectiveness of the product. The overarching goal of clinical validation is to demonstrate to regulators that the device will work, as intended, for target users.

For instance, for your SaMD to be approved as a treatment for individuals with a specific diagnosis, you’ll need to demonstrate that users with the target diagnosis achieve clinically meaningful outcomes through using your SaMD.

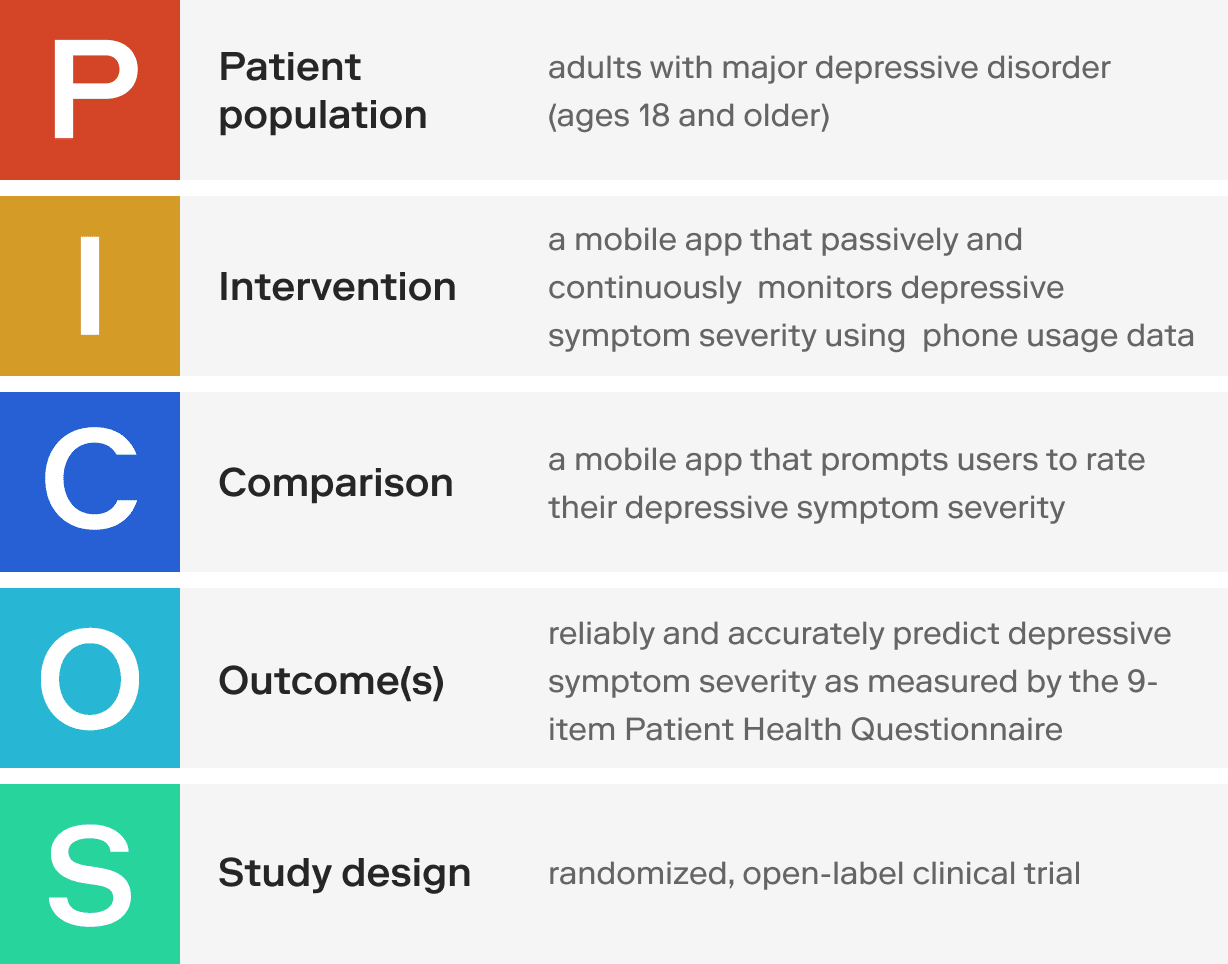

You can use the PICOS framework to frame your clinical trial:

- Patient population - What is your target patient population?

- Intervention - What is the “active ingredient” within your SaMD, without which it cannot serve its intended medical purpose?

- Comparison - To demonstrate efficacy or effectiveness in a controlled trial, your SaMD must be better than a comparator. You can forego having any comparators in your study design until you’ve collected enough data to warrant a controlled trial.

- Outcome(s) - What are the expected clinical outcomes?

- Study design - What is the most appropriate clinical trial design? In general, randomized controlled trials (RCTs) are considered the gold standard because they provide the highest level of evidence. However, RCTs are expensive and difficult to conduct.

💡 Developing a new SaMD with a well established clinical association saves tens (sometimes hundreds) of millions of dollars when compared to developing a new SaMD with a novel clinical association.

This is because it takes years to conduct clinical trials to demonstrate the safety and effectiveness of a SaMD in the absence of preexisting clinical evidence. Startups should consider creating a SaMD with relevant and high quality clinical evidence supporting the target indication.

If you must generate clinical evidence, don't expend all your capital on your first clinical study. Start with a smaller proof-of-concept clinical study to validate your hypothesis, and incrementally conduct larger clinical trials as you build clinical validation traction.

In this article, we’ll focus on how to generate clinical evidence to support a premarket submission, beginning with a general overview of how clinical trials work (and how to think about your SaMD from a clinical validation perspective), and concluding with how you can get started on clinically validating your product.

1. Define product scope

Use the PICOS framework to shape the scope of your SaMD.

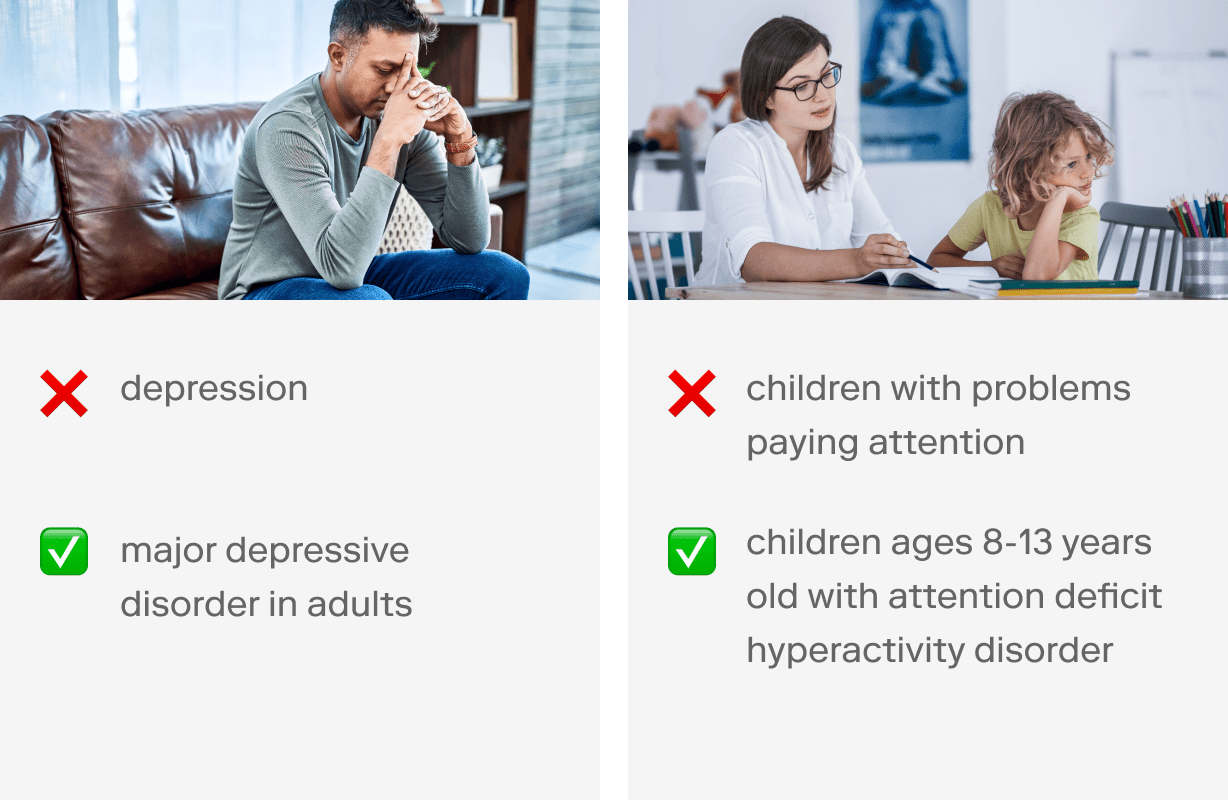

What is your target patient population? You must be very specific in outlining relevant inclusion and exclusion criteria based on your target indication.

💡 Try to be as specific as possible, without being too narrow. (More on this in step 3 below. 👇) Here are some examples:

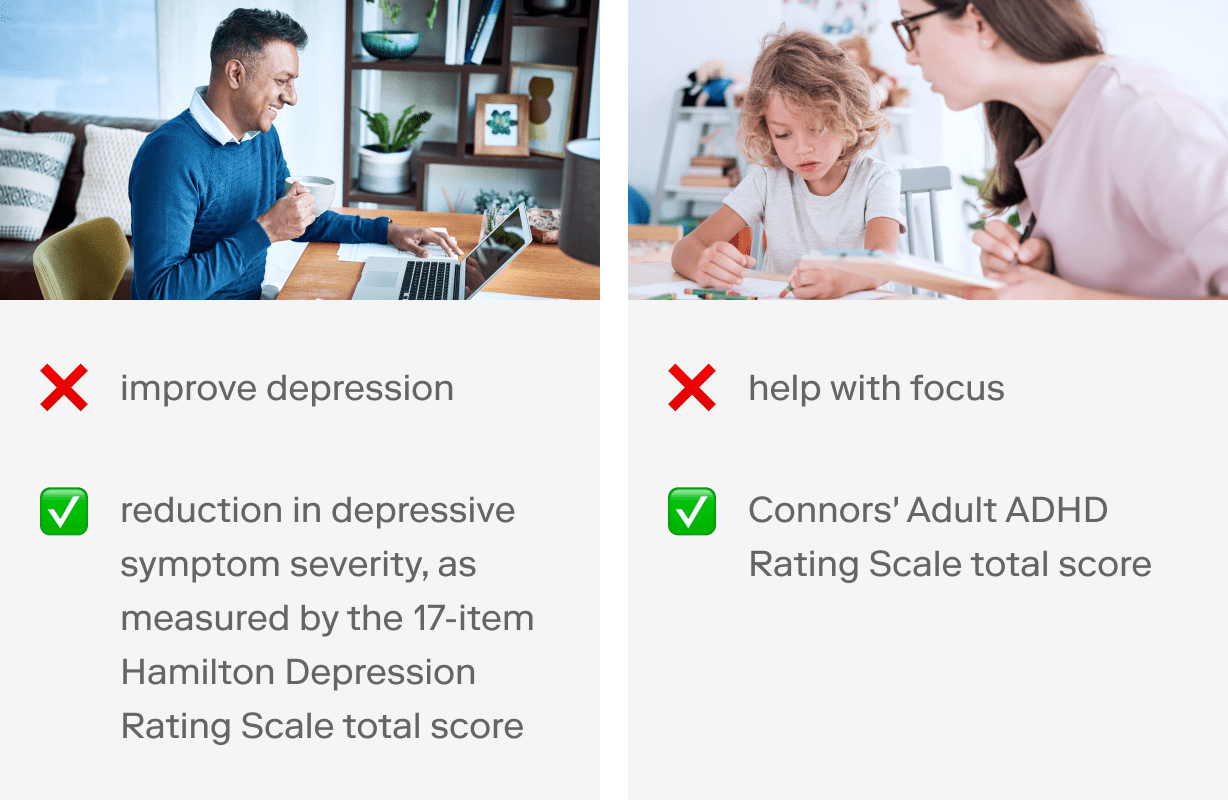

What are the expected clinical outcomes? Operationalizing your clinical outcomes is critical to demonstrating that your SaMD achieves its intended medical purpose.

💡 Use an outcome measure that has been validated in your patient population. (Also more on this in step 3 below.) Here are some examples:

You should also consider the type of product you are developing. Are you creating a diagnostic test? Do you plan to develop a treatment? This will determine your SaMD classification and the rigour of documentation and evidence regulators require.

💡 Find the product monographs of medical devices or drugs that have been approved for a similar indication. What inclusion criteria are outlined under Prescribing Information? What are some contraindications? Scroll down until you find information about pivotal clinical trials. What outcome measures did they use?

You can look up the eligibility criteria of clinical trials registered on clinicaltrials.gov or the EU Clinical Trials Register, for example.

Expertscape is a great way to identify thought leaders in medical research. (You can even filter by country, city, subspecialty, and more. See this example to find experts in depression research.)

2. Determine clinical validation requirements

To instantiate a clinical association between your SaMD and your intended use, you can use existing clinical evidence or generate new clinical evidence (e.g., perform clinical trials) supporting the safety and effectiveness of your SaMD.

💡 If the clinical association is well established and widely accepted within the medical community, you may not need to conduct your own clinical trials.

Before commencing your own clinical trial, you should always comprehensively assess what clinical data are available to support your claim(s). You may be able to leverage professional society guidelines, peer-reviewed data from completed clinical trials, and other sources of existing clinical evidence to support your premarket submission.

If you’d like to learn more about how to find and leverage existing clinical evidence to support your SaMD, subscribe to receive our next article in the SaMD Clinical Validation series.

The degree of clinical evidence required to support your SaMD depends on your product scope and the clinical landscape and will largely determine how long (and resource intensive) your runway to marketing authorization is.

Pharmaceutical companies start planning clinical validation by talking to regulators, and so should you. Begin those conversations as early as defining the scope of your product(i.e., step one above), especially if you’re building a SaMD based on a novel clinical association and/or without a predicate device.

📚 Predicate device: an existing medical device to which equivalence can be drawn to obtain marketing authorization for a new medical device

Understanding the relevant clinical validation requirements for your SaMD is key to evaluating whether the product is feasible and viable, for your customers and regulators alike (which we call product-regulatory-market fit).

👀 Want to learn more about product-regulatory-market fit and product management strategies for SaMD? Come to our meetups!

3. Begin planning a study protocol

Here are some key questions to get you started.

How will you measure your target clinical outcomes? Have the identified metrics been validated and demonstrated sensitivity to change in your target population in previous clinical trials?

📚 Sensitivity to change: the ability to detect and meaningfully quantify longitudinal change.

How will you operationalize clinically meaningful changes in your primary and secondary outcome measures?

📚 Primary vs. secondary outcomes: a study protocol typically identifies one outcome measure as the primary outcome measure, and one or more outcome measures as secondary outcome measures before starting the study. A clinical trial that fulfills its primary outcome criterion is said to have a positive outcome (the opposite is true of a clinical trial with a negative outcome).

Have comparable clinical trials previously demonstrated clinically meaningful change using the same outcome measures?

📚 Clinically meaningful change: positive impact on the health of an individual; the threshold for a change to be clinically meaningful is based on a minimal clinically important difference (MCID) analysis and varies across metrics and outcome measures.

What is the appropriate study intervention period? How long do patients need to be exposed to the intervention to experience clinically meaningful changes? What are your primary and secondary study endpoints?

📚 Study endpoint: a timepoint during the study intervention and/or observational period that is being used to measure clinically meaningful change. A study protocol must identify one timepoint (e.g., 4 weeks after starting a digital intervention program) as the primary study endpoint and can identify one or more timepoints as secondary endpoints.

How will you analyze your data? How many participants will be required to adequately power your study? Is this feasible (e.g., given your budget)?

📚 Statistical power: the probability a test will detect an effect when there actually is one. The more study participants you have data from, the greater your statistical power and the likelihood you will be able to detect a change that is not due to random chance.

Which study design is most appropriate for you, given your needs and available resources?

💡 There are faster and less resource-intensive ways to generate clinical evidence than conducting a clinical trial. For instance, small feasibility studies and non-interventional observational studies are not considered clinical trials and you can get started with appropriate research ethics approval.

For example, rather than building your entire app in the first iteration, isolate the most important component—the intervention—and build a minimum viable product. Instead of trying to validate your product in patients for the first time, start collecting feasibility or observational data (with appropriate ethics approval). This will allow you to validate your ideas in users much sooner than you could if you began with a clinical trial.

📚 Feasibility study: measures feasibility, rather than a health outcome, as the primary outcome

📚 Non-interventional observational study: does not prospectively assign participants to an intervention to collect health outcome data from individuals that are using a SaMD

How will you recruit and enrol participants? What do you need to access enough patients to enrol the target sample size?

The amount of time you’ll need to complete study enrolment depends on the number of clinical research sites you’ve partnered with, volume of patients at each site, total number of patients in the target geographical regions that fit your inclusion/exclusion criteria, intervention period length, and many more factors.

Your answers to these questions will form the foundation for your study protocol.

4. Prepare a clinical trial application

A clinical trial application includes your study protocol and dozens of documents required by regulators to obtain approval before commencing a clinical trial. Your study protocol outlines the steps needed to conduct the proposed clinical trial. It includes details such as the number of patients who will participate, the type of data collected, and the length of the study.

Once you’ve outlined the key aspects of your study protocol, you should meet with regulators for a pre-submission meeting. This will allow you to present your plans and documents and check that you’re on the right track before beginning to write a full clinical trial application.

💡 An experienced clinical research team can take 3-12 months from writing the first draft, to submitting for approval, waiting for review, revising, and obtaining regulatory approval.

Regulatory approval (e.g., US FDA, Health Canada) is required to obtain approval from a research ethics board. (Failure to obtain appropriate ethics approval will result in an inability to use your data to support your premarket submission application and publish your findings in peer-reviewed journals.)

Depending on the research ethics board you select, this step can take anywhere from one month to over a year. Private, community-based research ethics boards typically offer more frequent submission cycles than do institution-based research ethics boards. However, not all research sites will allow you to use private community-based research ethics boards; you should check with your study investigator(s).

💡 Once you have regulatory and ethics approval, a clinical trial can take as little as several months to 4+ years.

| Phase | Time | Number of participants |

|---|---|---|

| I | < 1 year | < 100 |

| II | 1-2 years | < 300 |

| III | 1-4 years | > 300 to a few thousand |

| IV | Several years | Several thousand |

5. Setting up a clinical trial

While you’re waiting for regulatory and research ethics approval, you can begin setting up the infrastructure needed to conduct your trial.

Pharmaceutical companies often use contract research organizations to conduct clinical trials. If you’re conducting your own trial, you’ll need to train staff with appropriate credentials and expertise, set up clinical research forms (CRFs) and a data repository, recruit participants, and more.

If you’ve never conducted a clinical trial before, you must partner with someone with experience. Clinical trials are highly regulated; they must be led by a qualified study investigator, and comply with Good Clinical Practice (GCP) requirements.

Conclusions

You should always start by looking for clinical evidence that are available to support your premarket submission.

If you need to generate clinical evidence, you should begin with a small, proof-of-concept, open-label study to incrementally validate your hypothesis and intervention.

As you build momentum and collect clinical evidence, you can conduct a clinical trial, with progressively more participants and/or interventional arms. This is our traction-first approach to building SaMD.

If you have any questions about your regulatory pathway moving forward, need help finding funding for your SaMD, or aren't sure how to find and leverage existing clinical evidence, join our SaMD community on Meetup and LinkedIn to learn more.

We’ll be hosting regular meetups to discuss various topics and ideas around SaMD. You can also contact us to let us know if there’s anything specific you’d like to learn about.